- Home

- Yeadon, Jane

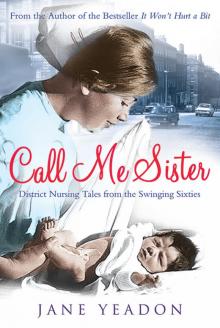

Call Me Sister

Call Me Sister Read online

To Isean Agam

Doorstep

Baby shoes, to heels and hob-nails,

I have lifted four generations

through the front door.

Scoured with hard-worn hands,

I roughen women’s knees,

but am caressed by their skirts.

Husband and wife sit sharing

a cigarette, the entwined smoke

lengthening the last minute dark.

Imprinted with leavings,

the beginning of every journey,

I am a clear path, a stepping stone.

Helen Addy

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Black & White Publishing for their unending good humour and guidance, Dr Harry Morgan for his Gaelic expertise, Clio Gray her wise words and Helen Addy for her poem. I must also thank Alister, my Brora wordsmith, and my pals in for Words, the Forres writing group.

CONTENTS

TITLE

DEDICATION

POEM

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

1 SHORT RATIONS

2 ROSEMARY FOR REMEMBRANCE

3 A NEW ADVENTURE

4 TRAVELLERS’ PROBLEMS

5 SISTER SHIACH SHOWS THE WAY

6 ON THE ROAD

7 COLD COMFORT

8 TAKING THE PLUNGE

9 MEN MAY WORK

10 A FATHER’S ROLE

11 A SEVERED HEAD

12 A LITTLE DRAMA GOES A LONG WAY

13 SOLE OPERATOR

14 POULTRY MANAGEMENT

15 PROGRESS OF A KIND

16 DOG CONTROL

17 RESCUE PACKAGE

18 A VISIT TO EASTER ROSS

19 FOG AND ICE

20 DELIVERY SERVICE

21 29 CASTLE TERRACE

22 PAPER CHASE

23 HILDA SHOWS HOW

24 IT TAKES ALL SORTS

25 LONG LIVE THE QUEEN’S POKES!

26 TIME FOR SOME PATIENTS’ SUPPORT

27 CATCHING UP

28 ALL CHANGE

29 A DAY TO REMEMBER!

30 RESCUE PARTY

31 NOT QUITE ALL IN A DAY’S WORK

32 LOOKING FORWARD

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

1

SHORT RATIONS

It was a bad start to a Monday. The teaspoon count hadn’t balanced and a bacon rasher had gone AWOL. Inverness’s Raigmore Hospital could be heading for meltdown. With a fresh outbreak of nastiness in my female medical ward and its Sister Gall providing it, my dream of leaving hospital work for district nursing had never looked more attractive. After all, I was a qualified general nurse and midwife; I’d had six months’ experience working in a male surgical ward and was now completing another half-year in this one. But even if that was a fair amount of training, I’d yet to come across treatment for a pain in the neck.

Tempted to try throttling, I sat on hands itching to clamp them round Sister Gall’s immaculately white collar whilst she used her pointy finger to stab the distance between us. Given our cramped office space, I was lucky she wasn’t nearer. Unlucky she was here at all. She wasn’t due on duty until the afternoon.

She snapped, ‘As staff nurse, it’s your responsibility to make sure all equipment is in place and dietary requirements ensured. It’s jolly lucky I’m here. I bet you wouldn’t have even noticed important things.’ She thought for a moment. ‘Like spoons and missing food.’

November sleet tracked down the window that rattled in its ill-fitting metal frame. It let in a keen draught whilst giving out onto a complex of brick-built, single-storey buildings. They matched ours but instead of the casualty department which was on our side, there was a maternity unit based at the far end. The distance between the two blocks was tarred and only took a few minutes to walk, less if you could run in rain.

Built as a short-term measure during the Second World War, Raigmore had lasted longer than expected. But even now in the late Sixties a replacement existed only in the imaginations of the optimistic. Still, a teaspoon shortage might highlight the lack of progress.

‘Running a hospital’s not just about caring, you know. There are other things as important.’ Sister Gall’s shrill voice raised an octave higher. She was about to retire but wasn’t going to go with a whimper.

In a way, I admired her attention to detail. I just wished she was more like the sister in the orthopaedic ward opposite our one. With hair as unlikely a black as Sister Gall’s was a definite grey, she was bright, jolly and happy to make up any cutlery shortfall, knowing it would be reciprocated at some point when Sister Gall was off duty. Our wards shared the food trolley, cause of cutlery mix-ups, as well as the separating corridor.

This morning hospital porters were making it a busy road. As they bounced passenger-laden transport bound for theatre, physiotherapy or the X-ray department, their cheerful chat leaked through the ward’s heavy entrance doors.

As if offended by it, Sister Gall kicked the office door shut. ‘I want a word.’ She settled into her chair, jutted her chin, crossed her hands and checked her cap. Nailed into position by anarmoury of hairpins, it looked set for all weathers. My inner barometer diagnosed dropping mercury with a distinct probability of an imminent storm.

She drew breath. ‘That place opposite,’ she thumb-pointed, ‘is full of folk who, like you, have taken up this daft new sport. I expect you were doing it this weekend too. Skiing!’ She spat the word out. ‘Now, just think of that ward. I know it’s full of patients with broken bones. I’m only here this morning because I thought you might easily have become one of them, and then I’d have to operate with even more of a staff shortage.’

Shaking her head in bewilderment, she flicked open the Kardex, a patients’ record folder, and tapped a stubby finger against a patient’s name. ‘And it’s lucky I did. There was bacon sent from the kitchens for Mrs Mackay, but according to her she hasn’t had any breakfast.’

I went for a cool, ‘I didn’t give it to her because of her morning sickness. She’d just have brought it back up.’

Casting a disparaging look at the Aberdeen Training School badge pinned on my apron, Sister Gall fingered her own. It proved she’d trained at Raigmore, something she never failed to point out was superior to any other training hospital. ‘Our patient’s a diabetic,’ she said, ‘and once she’d got over that sickness nonsense, she could have had that bacon. We’d just have reheated it.’

I thought about our pale and retching patient. I’d been surprised she wasn’t in the maternity part of the hospital. Maybe they’d no staff. Maybe all their midwives had gone skiing and were stuck, injured or lost in the wild fastnesses of the Cairngorms, and maybe this wasn’t a good time to say so.

‘Right!’ I hoped my tone conveyed dignity and resolve. ‘I’ll go and make her a cup of tea and see if she can keep down some toast.’

But Sister Gall wasn’t going to give up. She barked, ‘She should have that bacon to make sure she’s getting the right number of calories.’

Exasperated, I went for broke. ‘Well, I threw it out.’

Her eyes narrowed and she looked crafty. ‘No you didn’t. I checked the bins and it’s not there and neither is the spoon.’

Crikey! She was hell bent on discovery.

Actually, I’d left the bacon on a plate in the ward kitchen. Remembering the rhythmic chewing of Mhairi, the ward maid, shortly after I’d told her Mrs Mackay would never eat it, I settled back in my chair and opted for honesty. Facing Sister Gall directly, I said, ‘Well, I don’t know where it is… now.’

With timing a second short of miraculous, the ward resident doctor stuck his head round the door. ‘Ah! Sister,’ he said. ‘Good to see you. I’m a bit concerned about Mrs Mackay. Looks a bit pale to me. Could yo

u come and have a look?’

‘I’m not supposed to be here.’ Sister Gall was coy. ‘But as you’re new here and if it puts your mind to rest, certainly. I’m always ready to help.’

Our doctor was tall and thin with a white coat so starched it made him look like a long pharmaceutically-wrapped parcel. Little Sister Gall in blue, resembling someone bundled into a square one, went off after him, having to hurry to catch up. I grabbed the chance to nip into the kitchen.

‘Muirst!’ (‘Murder!’) Mhairi’s Gaelic was as accurate as the mouthful of tea she aimed into the sink. ‘Is she still around? She was here going through the bins. I’d to keep well away from her. She’s got a nose like a bloodhound. For a moment I thought she might pass a tube down my throat to prove her suspicious wee mind. Has she not got a home to go to?’

‘The Old Folks’ one wouldn’t take her,’ I said, too irritated to be loyal. ‘Just don’t breathe near her, and see if you can get a spoon from over the way. Otherwise we’ll never hear the end of it.’

A student nurse and auxiliary were also on duty. I found them in the sluice discussing the Saturday night dance at the Caley, a popular hotel in town.

‘Loads of talent,’ said Student Nurse Black, whose name belied her blonde hair. ‘I was never off the floor. It was just great.’ She eyed me with kindly curiosity. ‘Have you a boyfriend, Staffie?’

I thought about David, newly graduated and working as a hotel manager in Glasgow. He made me laugh, shared my Morayshire background and had blue eyes that could have melted my heart, was it not so set on becoming a district nurse.

‘No,’ I said, ‘but I bet you’ve plenty. You could give me some of your spares.’

She laughed. She was bonny with a bubbly personality that made her an engaging addition to the staff. She had a soft voice, which seemed alien in the clinical surroundings of the sluice, and she also turned out to have a flair for floral art. Even Sister Gall seemed to appreciate a gift that brought life and colour to our spare quarters, based, as they were, in buildings one step up from Nissen huts.

‘Ach, right enough. I mind the days,’ sighed the auxiliary, emptying a bedpan and turning on a tap.

Sister Gall was obviously out of earshot, otherwise they wouldn’t have been having such a delightful conversation. Notwithstanding the Caley’s attractions, they seemed clear as to their duties so I left them and went to check on Mrs Mackay.

Unlike some of the wards with their long stretch, ours was broken up into six-bedded units. These gave increased privacy, but Mrs Mackay, with her substantial bump and youth, looked out of place amongst the other patients, many of whom were old and determinedly snoring.

Soon, I thought, we’ll be getting them out of bed. They won’t want that, and who could blame them? Sitting in a draughty corner, looking at the ward’s green-painted brick walls didn’t hold much in the way of improved prospects, even if it shifted pressure off their bums and helped prevent bedsores.

Mrs Mackay sat up in bed and punched her pillows. ‘I’m such a nuisance,’ she declared, pushing back a tangled rope of black hair. ‘Sister Gall was cross I couldn’t eat my breakfast, but I just can’t face anything greasy first thing in the morning. I did tell her but she wasn’t for listening. She was in right bad tune. I hope you didn’t get into any trouble?’

‘No, no. She’s just anxious to get your diabetes under control. But maybe you could eat a slice of toast now, and what about a cup of tea?’

‘Oooh!’ She winced and put her hand over her bump.

‘You sore?’

She shook her head. ‘Just a wee twinge.’

I put my hand on her stomach and felt it tighten under my touch. ‘Mmm. Tell you what, you have a go at some tea and toast. I’ll get someone to make it for you.’

She looked anxious. ‘Anything wrong? With this being a first, I don’t know what to expect, but Nurse,’ she said, grasping my arm in a surprisingly firm grip for someone so gentle and undemanding, ‘it’s not due until the end of next month.’

‘Did Doctor or Sister examine you?’

‘Well, they took a urine sample and my pulse, but now you’ve got me worried about the baby. Next thing it’ll be my blood pressure.’ Mrs Mackay sighed and bit her lip. There was a sheen of sweat on her forehead. Maybe she was hypoglycaemic. Too much insulin could do that. Oh dear! She definitely needed something to eat.

A year ago I’d qualified as a midwife in Belfast. The Royal Maternity Hospital’s work was so specialised a normal delivery was a surprise. The training had been hard work, with plenty drama. I’d thought I’d have a break from it so the last thing I expected in a medical ward was this.

I said, ‘I’m sure everything’s fine, but I’ll come back in a minute and have a wee look. It’s maybe worth checking.’

* * *

I needed to see Mrs Mackay’s notes and was so sure Sister Gall had gone, it was a surprise finding her in the office mulling over them with the doctor. Frowning, she looked up. ‘Shouldn’t you be dressing that bedsore?’

So much for patient care and identity! I wondered if nursing for as long as she had had made her forget she was there because of patients. Maybe over a period of time in the same hospital surroundings you could be so taken over by inventories you could become lost to patients’ needs. I hoped I’d never lose sight of the fact that they had names, and the one with the bedsore was Miss Caird.

She was an old lady who lived in an isolated house in an Inverness-shire glen. Noticing a lack of lights in the home, a neighbour had checked on her. When she found her in bed, dehydrated, emaciated and with a foul-smelling bedsore, she immediately sought medical help. Miss Caird was confused, but nobody was sure if that was due to her present state or because she might already have dementia.

‘She’s never been one for company and she’s seemed to be getting even worse. Lately it’s got so she wouldn’t allow anyone near the place,’ explained the neighbour who’d found Miss Caird. Glancing round the ward, she added, ‘And she’d never have been here if she’d been conscious. She’ll no like it here at all at all.’

Even if she was screened off and the other patients spoke quietly, how could she? This must be a planet away from her own world, where the elements prevailed. Now, under our care and a ceiling of peeling plaster, she lay quiet and undemanding. Only a faint gleam in the faded blue of her eyes when anyone spoke to her showed she had an awareness of sorts.

Her infected sore demanded the sort of attention which made it all too easy to forget the sufferer. I understood why a trained member of staff with a stomach less queasy than a student’s should have to deal with this, but not why Sister Gall always made herself exempt. Still, she was supposed to be off duty at the moment and I was meant to be in charge.

I knew the dressing needed to be done, but it would take time, our most limited commodity. Reckoning our pregnant patient was a priority, I persevered with my audience. ‘I’m not sure Mrs Mackay’s contractions are Braxton Hicks. They’re usually painless, but I think she’s feeling these ones.’

Sister Gall and the doctor looked puzzled, so I continued. ‘We wouldn’t want to risk a delivery here, especially with a diabetic.’

Sister Gall shuffled some papers in exasperation. ‘Instead of frittering away your time, I suggest you go and do that dressing as I told you to do ten minutes ago. Mrs Mackay was fine when we saw her, wasn’t she, Doctor?’

The doctor, looking worried, nodded. ‘Of course, I’m not up so much on midwifery. Unless we wanted to specialise in it, our training didn’t cover it in great detail. Maybe if Nurse Macpherson’s a trained midwife, we should be listening to her.’

‘What?’ Sister Gall was shocked. ‘Mrs Mackay’s here to have her diabetes stabilised, not to have a baby, and Nurse Macpherson’s here as a staff nurse in a medical ward. Good gracious! I’ve never heard the like. Anyway, the diabetic consultant’s coming in this morning. He’ll know best.’

‘Will he be coming soon?’ I wondered aloud.

<

br /> ‘Soon enough. Now just get on with the other work. There’s a whole ward to run.’

‘Yes, Sister.’

Miss Caird lay so still that for a moment I thought she might be dead, but her eyelids fluttered when I touched her cheek. ‘I’m coming to see you soon,’ I whispered. ‘I’ve just a wee worry on at the moment.’

I got back to Mrs Mackay. She was now looking so uncomfortable that I began to really fret.

‘Is your tummy tightening regularly?’ I asked, noting the unfinished tea and half-eaten toast.

‘Everything’s fine, isn’t it?’

‘Oh, just dandy. But just to be sure, let’s have a look at you.’

A quick examination was enough. And enough was enough. Holding out her dressing gown and slippers, I said, ‘Come on, Mrs Mackay, you climb into these whilst I get a wheelchair. We’re going on a trip and it’s from here to Maternity.’

2

ROSEMARY FOR REMEMBRANCE

I was in such a hurry to get Mrs Mackay wheelchaired over to Maternity, I nearly ran over Sister Gall. She must have heard the sound of the racing wheels because she shot out of the office. She looked furious.

‘Can’t stop,’ I said, knowing that if I did, things could become undignified. I’d just have to deal with her when I came back. Right now, that wasn’t a priority. Certain that our patient was in labour, I knew that, once delivered, her baby would need special care and probably in an incubator. When I got back, and reasoning that this might strike a chord, I’d say to Sister Gall, ‘And as far as I’m aware, that’s not part of our ward’s inventory.’

Between silently practising the lines and assuring Mrs Mackay that we hadn’t quite reached the sound barrier break point, we arrived at the Maternity Unit. It had been a long sprint and by the time I handed over my charge, I was quite out of breath. Struggling to get it back before returning to Medical, I rehearsed my putdown lines but could have saved myself the bother. My senior had stomped off, saying she’d had enough for one morning. We’d see her in the afternoon.

Call Me Sister

Call Me Sister