- Home

- Yeadon, Jane

Call Me Sister Page 2

Call Me Sister Read online

Page 2

So, now and having the time, I attended to Miss Caird. As I dressed a dreadful sore that demanded every skill I could muster, I packed the foul-smelling space where there had once been flesh. I looked for some sign of healing; it’d be a gauge on her health. There was none. Any point of contact now seemed to bruise her skin whilst, under its translucence, her veins mapped out their blue, tortuous routes.

A simple arrangement of flowers stood in a vase nearby. Nurse Black must have put them there, as well as provided the tartan ribbon tying back Miss Caird’s lank grey hair. I feared it was too late for her to notice those small kindnesses. With her weak pulse and shallow breathing, she seemed to be drifting downwards and ever faster from us.

I wished I knew more about her. There were no clues from the few possessions stored in the old-fashioned metal locker parked beside her bed. Her neighbour had brought them in and she was her only, but occasional, visitor. She knew little other than what she’d previously told us.

‘Private and proud,’ she’d reiterated, shaking her head. ‘Private and proud.’

Aware that even if Miss Caird seemed far away, she might still hear things going on around her, I settled for a one-way conversation. ‘One of our patients has gone over to Maternity. I think she was a bit surprised. You see, her baby isn’t due for a while. We’ve just to hope everything will be fine.’

Although there was no response, I sensed she was listening, so I carried on. ‘They’re awful busy over there so I don’t suppose they’ll have time to let us know how she’s getting on. But when I go off duty I’ll nip along to Maternity, find out, and then I’ll come back and tell you.’

It didn’t take that long.

Sister Gall made her official return, looking as if she’d been caught in the rain. She was drying her spectacles whilst her cap had little blotches on it, making it look a little less starchy. It was even a little askew. Replacing her spectacles but avoiding eye contact, she sounded subdued as she said, ‘I went over to check on Mrs Mackay before coming on duty. You were right. She was in labour.’ She sighed gustily. ‘She’s had her baby and it’s a girl.’

‘And how are they?’

‘She’s OK. Worried about the baby, of course. I went to see it. It looks too big to be in an incubator.’ Referring to the baby as an ‘it’ seemed to give Sister Gall slight satisfaction. She was beginning to pick up speed. ‘Makes you wonder if they know what they’re doing over there.’

I thought I might say diabetic mothers’ babies were often big and would soon lose the extra fluid they carried and return to a more normal weight. Considering Sister Gall’s recent learning curve, I decided that although she hadn’t done midwifery training herself, she’d probably had enough for one day and she’d appreciate a return to familiar ground.

‘I’m sure they’ll both be fine, but actually I’m more worried about Miss Caird. She’s really going downhill.’

Like a circus horse smelling sawdust, Sister Gall perked up. She sat up straight and lifted her chin. ‘Right. You go back, keep an eye on her and I’ll tell the doctor. We can’t have her suffering.’ Already she was on the phone.

I was right to be anxious. Our patient had become flushed, restless and was muttering in a different language. It could be Gaelic. I couldn’t understand it but Mhairi probably would. While waiting for the doctor, I decided to ask her.

She looked surprised but pleased. ‘Gu deibhinin (certainly), it’s my native tongue!’ she said, drying her hands and coming with me. ‘It’s when I speak from the heart.’

I could see that. After listening closely to Miss Caird and murmuring back some Gaelic words, she translated. ‘She says she’s going to die.’ With an awkward hand, she soothed Miss Caird’s brow. ‘I’ve told her to be brave and she’s in good hands, but look, Staff, she’s frightened.’ She pointed to tears streaming down Miss Caird’s with ered cheeks.

I felt awful. I should have realised she was in all probability a native Gaelic speaker. No wonder communication was poor. Now it seemed time was moving too fast for me to make up for a lost opportunity. She probably never understood a word I was saying. Settling for the next best thing, I whispered to my interpreter, ‘Mhairi, could you tell her about Mrs Mackay and her having a baby and we’re sure everything’s going to be all right.’

The ward maid bent down and relayed the message. It sounded like a lullaby. The only sign that Miss Caird might have heard was her faint muttering. Now the other patients, never loud at the best of times, fell silent. It was as if they were all holding their breath and listening.

Then, Sister Gall’s stubby fingers pulled back the surrounding screens, their rail-fastenings rattle, breaking the silence. One look at our patient and after a brief exchange of glances with the doctor, she took over.

‘Right, Miss Caird, It’s a bit busy round here and you need plenty rest and something to help your pain, so we’re going to move you into the wee room opposite my office. It’ll be easier to keep an eye on you there.’ Grasping the rail at the head of the bed, she said, ‘Right, Doctor, you take the other end, and, Staff,’ she gave me a nod, ‘you can get on with the rest of the work.’

With the screening curtains swept back and Miss Caird moved out, the ward’s other patients moved into a chattier mode. Later that day, a stroke victim would fill the space left by Miss Caird. She’d be surrounded by an anxious family who were either thronging every corner or jamming the hospital telephone line demanding a progress report. Sister Gall found them a pain and a lot more difficult than the care of Miss Caird. But soon that wouldn’t be needed either and the room opposite the office was emptied. One day, as quietly as she had come, Miss Caird drifted away.

It’s a sad fact but all nurses have to learn to cope with death. This would be Nurse Black’s first one. I supposed that I’d be the one helping her handle it, but Sister Gall shook her head. She said, ‘I’ll take her and show her what to do, but it’s a traumatic enough experience without her having to see that awful sore. Will you make sure it’s covered before we start? She’s a good wee nurse and we don’t want to lose her.’

Was it my imagination or was there a slight softening in Sister Gall’s steely approach? Her consideration was as unexpected as was the tone of the dressings request. Afterwards, Nurse Black’s reaction to the experience was unexpected as well.

She was in the sluice putting fresh water into a vase of flowers. Concentrating on drying the base, she mused, ‘Don’t you worry, I’m fine, Staffie. And you know, I was dreading dressing a dead body and I certainly didn’t expected Old Gallstone to be anything but practical, business-like and totally uncaring.’ She sniffed hard then continued. ‘And of course Miss Caird was a very private person. But Sister Gall dealt with her as if she was still alive and gave her the respect and dignity I’m sure she’d have wanted. Honestly, she made the whole business seem easy but right. And she let me use rosemary,’ the young student finished with a note of triumph. ‘After I told her it was a herb for remembrance she let me weave a sprig of it through Miss Caird’s fingers. It made them look almost alive. I felt it was a good way of saying goodbye. What d’you think, Staff?’

Linking her arm in mine and handing her a tissue, I said, ‘I can’t think of a better way of marking your care. It shows that someone we thought unknown who kept herself to herself will never be forgotten. And I’ll never forget you for your tribute.’

3

A NEW ADVENTURE

‘So, you’ll be off skiing, I suppose?’

Sister Gall was doing her best. We were in the office and after giving her the handover report I had a day off. Since Mrs Mackay’s transfer to Maternity, the ward sister had softened a bit, at least enough to consider her staff might have a life outwith food calorie and cutlery counts. She had even begun to trust me to run the ward when she was off duty.

Toning down the criticism she’d so easily given before must have been difficult. It would be a shame for me to lose this goodwill, but it was sure to go if I were to

tell her I’d applied for a district nursing job in Ross-shire. I’d be spending my day off having an interview in the county’s headquarters which were in Dingwall, twenty miles north of Inverness.

My sister Elizabeth and I had two maiden aunts who used to live there. When we were on our summer holiday staying with our granny in Nairn, the highlight was to visit them. I don’t know why we never went by train. It would have been possible, and quicker. Maybe Granny’s Calvinistic spirit rejected the idea of ease, leading her to declare with exasperation, ‘You’re both such poor travellers. I hope you can make it at least as far as Inverness without actually being actually sick. When we change buses there, you’ll get a break. That sometimes helps.’

What she actually meant was that puking into a paper bag was one thing, but holding on to allow a timely sprint to the bus stop toilet showed fortitude – and a paper bag saved for the second half of the journey. Break or not, the journey seemed to last forever. When we did eventually arrive at our aunts’ house, we were queasy. We smelt of petrol and cigarette smoke, but their welcome was absolute, if dangerous.

‘Come in, come in!’ They’d cry, throwing open their thin little arms. Then Nanny, the eldest, would shepherd us towards, then make us sit down at a small, round and very unstable table. Covered in an exquisitely hand-embroidered linen tablecloth, it would be groaning with food. ‘You must all be starving. Look! We’ve had a lovely morning preparing this. We’ve even made sausage rolls ’cos we know what wee lassies like, don’t we, Jessie?’

‘Yes. Lemonade too, and after everything’s been scoffed, we’ll have a wee concert. Your granny tells us you’re wonderful dancers.’

With a sly look at this unexpected promoter of our talents, Nanny put in, ‘Singers too.’

She was so enthusiastic we could only oblige. Well into her spinsterhood, perhaps Nanny was looking for some recognisable genetic imprint in us. It certainly wasn’t in looks, for neither aunt had my red hair and freckles nor Elizabeth’s dark curly hair. Instead, tortoiseshell-backed hair clasps held back faded blonde hair from their pale serene faces.

The aunts scratched a living teaching country dancing and were good teachers, accustomed to the space of the halls where they taught. Bothered by stage fright and shyness, my sister pointed out the limitations of their minute sitting room.

‘Och don’t be shy,’ encouraged Nanny. ‘Look, you. We’ll move the table. You’re not big girls. We’re sure you’ll manage. Just don’t dance too near the glass cabinet.’

With Jessie playing the piano and Nanny providing illustrative footwork on the neatest and lightest of pins, we were inspired to dance and warble. Under praise heaped on by two gentle souls, schooled in tact, we grew cocky. We leapt imaginatively and ever higher until the glass cabinet ornaments put in a protest.

Catching the aunts’ anxiety, Granny rose. ‘Time to go,’ she said. ‘Come along, girls. Getting back to Inverness itself, never mind Nairn, takes time.’

She was right then, but now as I drove my Hillman Imp out of Inverness, the way seemed familiar but shorter. The road still wound its way along the Beauly Firth with the railway track making the occasional snaking companion alongside, whilst the sea waves still left old lace frills on the shore. In the distance seabirds floated in a line on the water, looking like a musical score.

The Rosemarkie transmitter was clearly visible on the skyline. When we were growing up on an upland Morayshire farm, we had a clear view of the Moray Firth. The sudden appearance in 1957 of an eye like a Cyclops on it astonished us, particularly as it turned out to belong to a transmitter clearing snow from our telly screens. As it was responsible for such a miraculous effect, I hoped that without the sophistication of a car radio, it would also help my tranny to work. I switched it on, hoping it would take my mind off interview anxiety.

“You can’t always get what you want,” sang The Rolling Stones. It was a bit different from “How much is that doggy in the window?”, a song my aunts swore was their favourite tune.

‘We could sing it again,’ I’d volunteered, eager for even more praise.

‘No, don’t! It was so good the first time, you couldn’t better it,’ said Granny, fumbling with her hearing aid.

I bet she’d have been surprised that I’d actually found such a doggie in Dingwall. And in a window! Driving into the county headquarters car park, I glimpsed a small black one sitting in the front of a Morris Minor already there. It watched with cocked ears as the driver climbed out. She wore a district nurse’s uniform and had the competent look of someone who if you asked for directions would give them clearly and concisely. The pillbox hat worn at a jaunty angle and the fish net stockings suggested, however, that there was more to her than map reading.

‘You mind the car now, Jomo,’ she said, shutting the car door. Right away, the little dog jumped into her seat and, putting paws on the steering wheel, looked out of the window with the enquiring eye of a professor. The car horn sounded once. Looking round and evidently satisfied with what he saw, he settled down.

She’d such a friendly, open way. I felt I could ask the question.

‘Jomo?’

‘Kenyatta, of course,’ she replied. ‘It had to be, with his colour and wee beard.’ She took in my suit, chosen because of its restrained colour and hem length, and smiled. Tightening her blue gabardine coat against the chilly November wind snarling about us, she said, ‘And I suppose you’re here for your interview? Come on, I’ll take you to Miss Macleod. She said you’d be coming.’

The everyday sounds of a council department were very different from those of a hospital, and whilst the corridor floor had the same gleam (proving the industry of dedicated polishers), the place felt warm, relaxed and welcoming.

I glimpsed staff through half-open doors and heard their easy chat. Amongst the notices on the doors, one said ‘Sanitary Inspectors’ and ‘Architects’. It looked an unusual combination but the chaps lolling over their desks seemed to be sharing banter in an atmosphere conducive to a stress-free day.

The proximity of Medical Officer of Health to Superintendent of Nursing made more sense. My companion tapped on a nameplate, then opened the door.

‘Morning, Miss Macleod. I’ve someone here I know you’re expecting,’ she said.

‘Come in, come in.’ Miss Macleod got up a from behind a mighty desk she shared with a Bakelite telephone and a black Conway Stewart fountain pen lying beside a rocking blotter. She was tall and her straight skirt was shorter than mine, her shoes a lot less sensible. She was elegant, friendly even. She stretched out a lily-white hand, so smooth it would have scandalised Sister Gall.

‘You’ve met Sister Shiach, I see.’ She gave my companion an approving nod. ‘She takes all our new members of staff for a few weeks. Shows them the ropes and, I have to say, she’s also Dingwall’s finest asset.’

Sister Shiach waved a dismissive hand. ‘Ach, away with you. There’s a few mums’ll no be saying that when I tell them their bairns have lice. I’m here to get some orange juice and hair shampoo for them. See if that stops them showing me the door.’ She tapped her hat as if to illustrate a thinking moment, then with a flash of strong-looking teeth, reversed out.

Miss Macleod sat down again. She leant against the navy-blue suit jacket slung across the back of her chair. She stretched her arms out so that she could spread her fingers on the desk.

‘You’re young to want to be a district nursing sister.’

Remembering the eighteen-year-old Nurse Black’s view that the next step for a twenty-three-year-old was hospitalisation in a geriatric ward, I was pleased about the youth bit but a little surprised at the sister emphasis. Eliminating ‘nurse’ from my vocabulary, I went for a cautious, ‘I’ve always wanted to be one.’

‘I’ve read your application. It’s come at a good time. We’ve actually got a vacancy for a relief sister.’ She tapped her fingers together in an approving sort of way. ‘And your qualifications seem suitable. I’m anxious to give the district n

ursing service a more youthful profile. You’ll have to go for the district nurse training, of course, but we’ll send you on the course if we take you on and when I see how you do.’

She frowned, straightened her shoulders then fixed me with a stern look. ‘Of course, too many people don’t think of us as highly trained professionals. They have a problem thinking of us as anything else but nurses when we have every right to be addressed as “Sisters.”’ She rapped the desk. ‘“Sisters!”’

Behind the classy spectacles her eyes were shrewd as she asked, ‘But always wanting to be a district nursing sister isn’t quite enough, so, could you expand on your reason for wanting to be one?’

I thought about my mother’s friend, Nurse Dallas. Her opinions and homespun philosophies were given great respect. She had a house, a hat that could hide bad hair days, a car, a dog, and people, including my strong and independently minded mother, took her advice. Who wouldn’t want that? She was simply named after the parish she served. I never knew her real name. But maybe the Dallas bit as much as the Nurse title would off end Miss Macleod. It’d be safer telling her about Miss Caird.

‘We need hospitals,’ I began, stating the obvious, but I had to start somewhere, ‘and by the time one lady came to the ward I work in, she couldn’t have been left at home. The trouble was, she was such a hermit, the hospital environment with all its staff must have been a nightmare to her. She was really ill before she was admitted and by the time she got to us she was past being able to make any decisions.’

I paused for a moment, hoping I was getting the right pitch. ‘But had she a choice, I imagine she’d have wanted to die at home. As it was, she was dressed in starched hospital gowns, surrounded by strange sounds and people who didn’t speak her language. It would have been so much kinder if somebody had been able to care for her, much earlier and at home.’ I bent my head, remembering that lost chance. ‘And I’d like to be part of a service that helps that to happen. Really worthwhile work.’

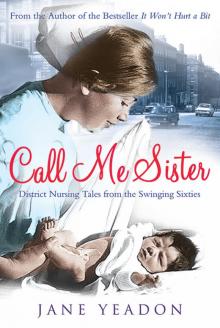

Call Me Sister

Call Me Sister